In memoriam: A special photo exhibit on the life and work of Shashank Srinivasan

Shashank Srinivasan

28 August 1985 – 22 April 2023

Shashank Srinivasan was a conservation geographer, robot operator, and cartographer who believed that technology, when deployed appropriately, could improve the wellbeing of the planet and its rich and varied life forms. After a successful career in conservation that included working with the Indian Ministry of Environment and Forests and WWF India, as well as pursuing an MPhil in Conservation Leadership at the University of Cambridge as a Chevening Scholar, Shashank planted the seed for what would become a pioneering new organisation leveraging technology in service of conservation. In 2017, Shashank founded Technology for Wildlife with a mission to amplify conservation through the use of modern technology. Over the years, Shashank led high-impact and collaborative projects and expeditions across the country, travelling with his team and fleet of trusted robots to map mangroves in Goa, count nesting Olive Ridley turtles in Odisha, and study endangered freshwater dolphins and crocodiles in the Gangetic Basin, among many other projects.

It was the profoundly spare and striking terrain of Ladakh, however – the closest a landscape came to resembling an alien planet, he often remarked – that captured Shashank’s heart and pulled him back into its valleys time and time again. For his Master’s thesis at the University of York, Shashank lived amongst and worked with the Changpa community near Tso Kar lake in Ladakh, investigating the impact of human behaviour on the magisterial, but endangered, black-necked crane. He returned to Ladakh a decade later, this time as a National Geographic Explorer, to document and capture the extent and distribution of litter in and around its many placid turquoise-blue lakes – of which two are known to be among the world’s highest – using aerial and underwater robots. In 2022, the Technology for Wildlife team returned to Ladakh to map the habitats of pikas and voles.

Shashank believed in the usefulness of drones as cost-effective tools to conduct research, especially in difficult terrain. But he was all too aware of the pitfalls of ‘technological utopianism’, often echoing the cautionary words of the author Kentaro Toyama: ‘Technology only amplifies underlying human intent and capacity’. If an environmental problem didn’t warrant a technological solution, Shashank didn’t recommend it. He also thought deeply, and consistently, about the ethics of drone use. He engineered projects and flight pathways that were attentive to the privacy concerns of local communities, and ensured that the wildlife being surveyed was always safe.

Shashank leaves behind an extraordinary legacy. As a conservationist, he brought originality, rigour, boundless enthusiasm, and compassion in equal measure to all that he did, driven at all times by a strong sense of purpose and desire for impact. In the photo story that follows, we share with you glimpses into his and Technology for Wildlife’s journey in conservation impact, with a special focus on drone-based work carried out in Ladakh in recent years. We are hopeful that these images, and Shashank’s unique story, will inspire a new generation of conservationists to take creative leaps forward to solve pressing environmental challenges using technology in meaningful ways.

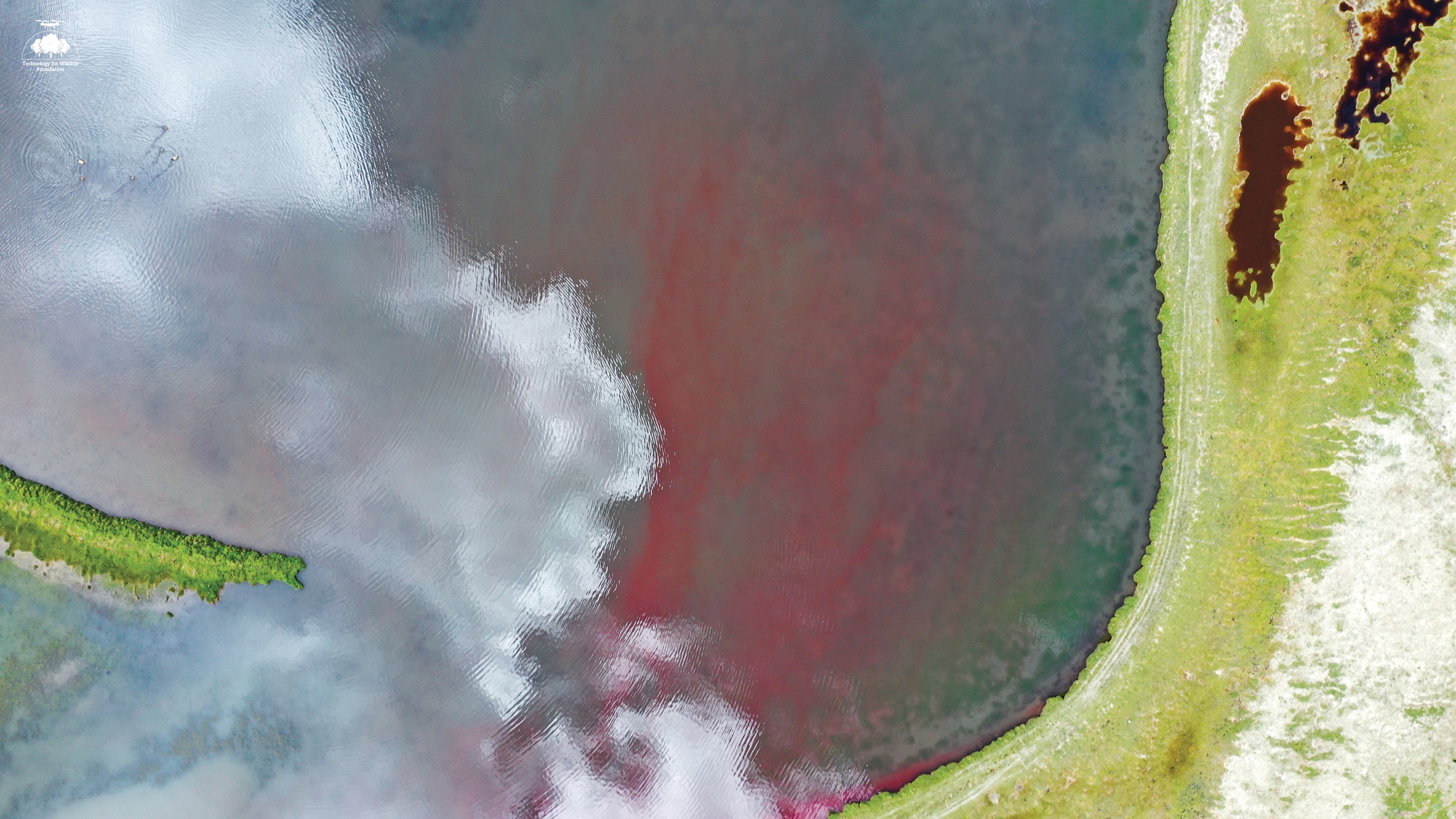

“These lakes act as oases in the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau, providing water to neighbouring wetlands and grasslands which in turn support endangered wildlife such as the snow leopard and the black-necked crane. However, the ecology in and around these lakes is threatened by unregulated tourism and the lack of garbage disposal facilities.” Shashank Srinivasan

For his Master’s field work in 2008, Shashank used predictive GIS modelling to assess the impacts of human activity on the spatial distribution, behaviour and feeding of the black-necked crane in the Tso Kar basin in Ladakh. His research concluded that, although the lifestyles of the local nomads did not significantly affect the black-necked cranes, it was possible that changing socio-economic conditions would increase pressure on the wetland habitat (breeding grounds for the crane) in the future. Increasingly aggressive tourism during the breeding period was also identified as a potential threat to established patterns and behaviours of the crane.

Experience in this landscape taught Shashank just how arduous and, quite often, dangerous it can be to conduct fieldwork at such altitude. It limits the possibilities of what can feasibly be researched or studied. In 2019, Shashank returned to Ladakh with a National Geographic Early Career Grant to capture these alien landscapes using machine perspectives. Underpinning this project was the principle that familiarity engenders understanding, and understanding births empathy – which is essential for driving conservation efforts.

The purpose of this project was twofold. Firstly, to capture visual images of these otherwise hard to reach lakes from different perspectives (aerial and underwater). Secondly, to understand whether, and to what extent, these lakes contained plastic contamination. Since none of these lakes have outflows, any plastic found here will remain and break down unless actively removed. Dive surveys are simply not possible in these lakes due to their extreme conditions and boat surveys would be very complicated to orchestrate. In other words, without this technological intervention, it would not have been possible to gather this data.

“Modern technology has made it possible to reduce the risk and complexity involved and with our equipment, it is possible to study these lakes for the first time with no risk to human life.” Shashank Srinivasan

During a mapping exercise in 2019, the team noticed that the video captures more than just beautiful scenery and plastic: it is a useful tool to study wildlife in the area. On the top left corner, one can see ducks present in the lake whereas at the bottom right, small burrows are visible. Exchanges with members of a research lab working in the area led to the co-development of a project to map the burrows of marmots, pikas, and voles in Ladakh using drone technology. These are wildlife of the squirrel family whose habitat is threatened by climate change. Mapping and marking their burrows using drones and computer vision is a useful way to track these changes.

The text and images have been curated by Supriya Roychoudhury and Nandini Mehrotra. They can be reached at supriya.roychoudhury@gmail.com and nandini@techforwildlife.com. For more information about Technology for Wildlife Foundation, please visit https://www.techforwildlife.com.